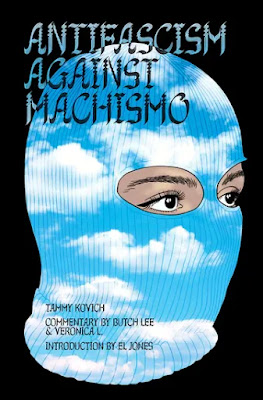

Tammy Kovich, Antifascism Against Machismo

With an introduction by El Jones and commentary by Butch Lee and Veronica L.

Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2023

153pp.; ISBN: 9781989701232

Review by D. Z. Shaw

In 2019, Tammy Kovich published, under the pseudonym of Petronella Lee, the short pamphlet Anti-Fascism Against Machismo: Gender, Politics, and the Struggle Against Fascism. Her essay is an important contribution to antifascist literature, which highlights how misogyny is a “fundamental pillar” of contemporary fascist movements, while making a compelling argument that gender liberation must be “a non-negotiable component of anti-fascism” (70).

When it was first published, Kovich’s reflections on militant antifascist organizing spoke to problems that many organizers had difficulty articulating. It is easy to dismiss critics who accused antifascist groups of being merely angry, blocked-up white dudes looking for a fight, because plenty of our experiences show otherwise. Antifascism is not about the optics, and if critics, the police, and fascists are on the wrong track identifying who antifascists are, who wants to correct them? But dismissing characterizations from outright opponents does not bring clarity to another, more difficult problem. Stanislav Vysotsky points out in American Antifa, his auto-ethnographic study of two antifascist groups (in two different cities) conducted between 2002–2005 and 2007–2010, that there was gender parity in both groups, as well as a high representation of individuals who identify as LGBTQ. (See pages 52-53.) Even if we acknowledge that an increased participation in antifascist organizing after the very public rise of the Alt Right in 2016 shifted the demographics of antifascist groups, I would argue that they remained relatively closer in composition to Vysotsky’s snapshots than the stereotyped, unsympathetic public perceptions. However, the persistence of machismo in these circles becomes even more difficult to untangle. Hence my first review of Antifascism Against Machismo (published in January 2020) focuses on Kovich’s critique of, and her proposals to overcome, machismo in antifascist organizing, and I believe her observations remain relevant today. (Three Way Fight also published a review of Kovich’s original pamphlet, by Matthew N. Lyons.)

Given the impact of the original pamphlet in antifascist circles, I greatly appreciate the publication of a new edition of Kovich’s Antifascism Against Machismo, which collects previously published commentaries by activists Butch Lee (from 2019) and Veronica L. (from 2020), with a new introduction by poet and abolitionist El Jones. By gathering these voices together, this new edition takes on an explicitly broader scope than the original, often shifting registers between a critique of the far right and of North American iterations of settler-colonial capitalism. Antifascism Against Machismo is a genuine discussion document, much like the multi-author text Confronting Fascism (also published by Kersplebedeb), opening new paths to militant organizing while challenging widely held or sometimes dogmatic assumptions shared on the left. As with any genuine discussion, not all questions are resolved, and thus we’ll circle back to a few at the end of this review.

* * *

The catalyst for the present review is Butch Lee’s commentary on Kovich’s essay. Lee is known for a handful of underground movement texts that work in and through an unorthodox Marxism-Leninism to develop a theory and praxis of revolutionary gender liberation, texts such as Night-Vision: Illuminating War and Class on Neo-Colonial Terrain (co-authored with Red Rover), Jailbreak Out of History: The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman and “The Evil of Female Loaferism,” and The Military Strategy of Women and Children. Her work has had an under-recognized influence on the three way fight approach, perhaps due to the fact that her analyses had not yet honed in on contemporary fascism and far-right movements. Until now.

From the start, Lee transgresses the narrow, pressing questions for antifascist work that animate Kovich’s original analysis. Lee moves between recollections of her early (and by her own account naive) activism, the patriarchal structure of capitalism, and neo-colonialism, surveying the terrain that gives rise to contemporary fascism. As Lee recounts, the problem of fascism first emerged as an urgent political issue within the Black liberation movement in the 1960s, epitomized by the Black Panther Party’s United Front Against Fascism conference in Oakland in July 1969. At the time, fascism was conceived as a form of widening and intensified political repression which nonetheless was “something not as different from but similar to ‘Americanism’ itself” (82). She suggests, without separating which is which, that analyses of the era “had both XL size insights and XL size misunderstandings”; now, “fascism/antifascism alike, there’s a new deal in the cards” (82–83).

Conventional leftist concepts of antifascism were cast in the late 1960s—not only when they draw from Black liberation movements but also when they characterize far right movements based on clichés from what Lee calls the “second-wave fascism” of George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party. System-loyal, “patriotic” groups that “fixated on anti-Black race hatred job one” (83). Groups which she characterizes as “tactically dangerous” (because of the threat of racial violence) but which were generally considered cosplaying outliers within their white racist American society. Theories of fascism that focus exclusively on state repression or dismiss street-level far-right movements as anachronistic sideshows completely miss the threat of contemporary fascism.

Contemporary, or what Lee calls “third-wave,” fascism is qualitatively different from the second-wave fascism of the 1950s and 1960s. It is system-oppositional and prioritizes both racial oppression and gender oppression. In contrast to the patriotic sentiments of the George Lincoln Rockwells of the bygone days of Segregation, third-wave fascism was born out of “Vietnam defeats, forced integration, and man-abandoning feminism,” and seeks to overthrow the U.S. government in order to reconstitute a white-settlerist, patriarchal society (86). And whereas second-wave fascism focused on anti-Black oppression, the new far right is “built heavily around woman-hating that joins their formative race hatred they are better known for” (90–91). Here, Lee commends Kovich for being “light years” ahead of conventional, mainstream accounts of far-right misogyny and misogynistic violence. First, Kovich shows that the “manosphere,” an online subculture of misogynistic discourses, overlaps with and functions as a pipeline toward fascist recruitment. Second, she outlines a spectrum of forms of fascist sexism from patriarchal fascism to misogynistic fascism. Finally, she catalogs how the far right now explicitly venerates violence against women. Lee concludes that supposedly individual or isolated attacks on women presage “targeting us eventually as an entire gender class” (87). (Though I feel like it is redundant to add, it is worth mentioning that for Lee those targeted for “gender class” violence under patriarchy include women, children, and LGBTQ+ communities.) She argues that women are “the first proletariat, the first conquered colony” of euro-capitalism, socially imprisoned and pressed into the labor of social reproduction (an argument made in more detail in her Military Strategy of Women and Children). Fascism seeks to revive the patriarchal recolonization of women’s bodies (101–103).

* * *

Lee challenges a common but unexamined assumption among antifascists: that militant antifascism engages in a limited or temporary struggle for community self-defense against street-level organizing by far-right movements; when this threat passes, the immediate tactical necessity for militant antifascist organizing dissipates, and the various individuals and groups who make up a local united front return to other types of radical political work. Both Kovich and Veronica L. make observations along this line, and on this point they are no different than other authors such as Mark Bray, Shane Burley, or myself. Sometimes these observations take on a more critical edge, but generally the cycles of antifascist organizing seem inevitable. Lee would certainly be familiar with variations on this theme during earlier cycles of antifascist organizing as well, for example, during the decline of Anti-Racist Action. So there must be something to this final verse before Lee has “sung [her] song” (115).

In my view, Lee makes two arguments to challenge the idea that antifascist organizing is a limited form of political work. First, Lee argues that the sexism and misogyny expressed by fascists are a small part of a much larger, growing and explicit, mass shift toward white right reaction (104–105). In other words, the confrontation with the far right doesn’t end in the streets. I think most militant antifascists would agree; indeed, we were critical of liberal antifascists when they decided to log off after Trump was deposed from power. However, I think Lee’s argument draws its political force from a second, largely implicit, line of argument. She writes:

What [Kovich] isn’t afraid to explore, is that women should lead our fight against fascism. Draw our own wider strategies. Make our own diversely talented groups. Because fighting fascism is a woman-centered struggle for our lives now. Antifascism is crucially about gender as well as race. (87–88)

The idea that militant antifascists return to their other militant political projects when the immediate threat of far-right movements taking to the streets abates, rests on a number of unexamined assumptions. Most importantly, we tend to assume that the politics of antifascist work parallels the politics of our “home” political circles, whether those are Marxist or anarchist, whether parties, affinity groups, or reading groups. However, what if gender liberation is truly integrated as “a non-negotiable component of anti-fascism” as Kovich justly demands? If fighting fascism becomes “a woman-centered struggle”? What home political circle can match this commitment to gender liberation, when the history of militant and revolutionary movements carries so much patriarchal baggage? Lee challenges a widely held assumption about the dynamic of struggle in order to point to a new political possibility for women-centered antifascist work. (J. Sakai recounts, from a different angle, what Lee considered a missed opportunity from an earlier period of political struggle in The Shape of Things to Come [Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2023] 359ff.)

* * *

By way of conclusion, I would like to highlight two issues that suffuse the discussions in the new edition of Antifascism Against Machismo: they concern the differing concepts of fascism and settler colonialism evoked by the participants. These problems are partially sketched in Veronica L.’s contribution and I would like to briefly revisit them here. First, none of the contributors puts a full definition of fascism on the table. Generally, the authors tend toward discussing fascist or far-right movements as types of white supremacy, but sometimes the discussion wavers. For example, near the conclusion of her essay, Kovich notes that “Black liberation and decolonial movements have either explicitly or implicitly been engaged in fighting against fascism for hundreds of years” (71). Such a claim, aside from the anachronism, confuses rather than clarifies the relationship of fascism and settler colonialism. It’s worth noting that Lee, who touches on the historical legacy of Black liberation movements’ antifascism while also sketching a sequence of historical waves of fascism, glosses Kovich’s claim with a subtle but important caveat that “Black people and Indigenous peoples and many others had been fighting something like fascism here from the start” (80, my emphasis). That something, of course, is white settler colonialism.

Through this discussion, a second problem emerges, when it becomes clear that the different participants in this intergenerational dialogue adhere to (at least) two different views of settler colonialism. Lee applies a Leninist anti-imperialist concept of colonialism to settler colonialism. Imperialism divides the world into oppressor nations and oppressed nations; settler colonialism differs from “classical” European colonialism (which maintained distance between the metropole and periphery) insofar as the colonies of settler-colonial states are internal colonies. According to this ‘old school’ paradigm of settler-colonialism all internal oppressed nations have a right to self-determination, and as we have seen above, Lee argues that women are an “internal colony” analogous to the situation of the New Afrikan nation. Veronica adheres to a ‘new school’ concept of settler colonialism (we are both writing within the Canadian settler-colonial context where this concept is current among activists), which draws its core distinction between settlers and Indigenous peoples, the latter which have the right to national self-determination.

Neither concept of settler colonialism entirely satisfactorily resolves questions raised by anticolonial struggle, and I believe there are difficulties translating the political demands made by one into the political language of the other. On the one hand, the new school concept, focused on the settler/Indigenous binary, encounters difficulties ‘placing’ the self-determination claims of a New Afrikan nation. On the other hand, Veronica questions the implications of an autonomous (white) women’s movement’s claim to “space” or land, a claim grounded in the old school concept, “in an anti-Black settler state that has from its beginning involved white women enforcing its hierarchies and advancing its settlements” (125–126). Indeed, if we widen the lens to a broader left’s organizational initiatives, squatting, occupying, or building commons are not inherently emancipatory or anticolonial in the settler-colonial context. The point of this comparison is not to adjudicate between the two concepts of settler colonialism, but rather, as Veronica notes, to highlight the ongoing work that needs to be done—even in the seemingly unrelated context of gender liberation and antifascist struggle.

Antifascism Against Machismo raises pressing questions about antifascism, feminism, gender liberation, and settler colonialism, through a genuine wide-ranging discussion between its participants. It is required reading for those interested in new directions for advancing militant antifascist work.