By Shane Burley

This essay is adapted from a talk delivered at the Territories of White Supremacy: Opposing the Far Right in the Pacific Northwest and Beyond conference in Eugene, Oregon on October 13th, 2023.

Before I talk about major updates that are happening for antifascists in the Pacific Northwest, I want to introduce three questions to help guide not only that discussion but all broad discussions of the future of antifascist organizing. The first question is what actually stops the far right, presuming that is our goal. There are a lot of tactics and strategies whose proponents say that they are capable in the fight against fascism, but this is always a matter of debate. What is provable, however, is that the tactics that work are ones that disrupt the functionality of far-right organization. This means tactics that break down the ability of a far-right group or movement to meet its goals, to reproduce itself, and to make gains. This can come in a number of forms, from canceled events, protests that disrupt meetings, or deplatforming. No matter which one we are talking about, the fulcrum of the tactic is the disruption since the presumption is that a far-right movement needs some continuity to have any degree of growth or victory. So the question of how we beat the far right is a question of how they are disrupted.

The second question is why we are fighting the far right. What are the values or vision for the world that leads us to want to see the far right fail? If we have a vision of a liberated world it necessitates fascists losing. But what is that world? What other features does that world have?

The third question, the more complicated one, is how question two relates to question one: how do our tactics to disrupt the far right help us to win a more liberated world? There are many ways to push back on the far right, many methods of disruption, but when activists pick tactics and strategy they are deciding more than just what works. Instead, they are trying to create a tactical set that is ethically and strategically sound for the larger questions of which antifascism is just one piece.

So, for example, it's quite likely that a police raid or FBI investigation and string prosecution can disrupt the far right. We saw this across the 1980s and 1990s as the FBI and ATF went after far-right compounds and groups, and even saw it more recently in the very severe sentencing handed down to the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers. But does increasing police funding, doubling up on FBI investigations, initiating severe penalties or terrorism sentencing enhancements get us to a more liberated world? The ways that antifascists take on the far right must be put in line with the why of the work: how do the decisions they make now lead to the world they hope to win? This should guide everything, from how and when tactics like “no platform” are applied to how their organizations function, how they build coalitions with other groups, and whether or not they prioritize care and mutual aid in the work.

“The ways that antifascists take on the far right must be put in line with the why of the work: how do the decisions they make now lead to the world they hope to win?”

When it comes to updates, there has been a lot of discussion of an alleged lull in far-right organizing and, subsequently, a delay in antifascist organizing. There have been fewer of the large, antagonistic rallies than we used to see frequently in cities like Portland, Oregon, but this does not indicate a decline on the far right’s side. Instead, this is a period of regrouping, rebranding, and reformation. This is similar to what was happening in many sectors of the white nationalist movement in the early 2010s where there were fewer incursions with antifascists, but this was also the time period in which people like Richard Spencer were building the alt-right. It was only in 2015 and 2016 that the increase really became visible, but this was after several years of base building. Those years of the alleged “lull” were where they made the peak of 2015-2017 possible.

A similar situation is happening now. The alt-right is largely dead, but certain organizations from that earlier generation have remained prominent. Patriot Front is the most important remaining one, which includes a heavy presence in Oregon. Because Patriot Front largely does flashmob style events or puts stickers up anonymously there has been less direct confrontation with antifascists, but there have been high profile releases of information when various Patriot Front chapters have been infiltrated by antifascists.

The groypers are, however, the largest inheritor of the alt-right’s energy, all centered on their leader, Nick Fuentes. Unlike the pseudoscientific and pagan infused alt-right, Fuentes has brought white Christian nationalism back into the hip center of the young far right. This has a tactical advantage for them since they are doing this at the same time as white Christian nationalism openly dominates the GOP. This has drawbacks and benefits: it allows them direct access to a whole new base of folks who are already a part of the larger conservative movement, but it also hinders their ability to differentiate themselves as a radical alternative. But they have done more than any other white nationalist movement in recent memory to win support in the Republican Party, particularly through their America First Political Action Conference (AFPAC).

Fighting the groypers has been a primary focus of antifascists, particularly on campuses in places like Florida, but the group has had somewhat less of a base in the Pacific Northwest. We have seen a sharp decline in the large public events from groups like Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys, with them diminishing steadily across events in 2020 and 2021. The last large attempt was in 2021 where a large antifascist coalition pushed them away from holding their rally in a city center and they ended up holding a small gathering in the parking lot of an abandoned K-Mart at the edge of the city.

|

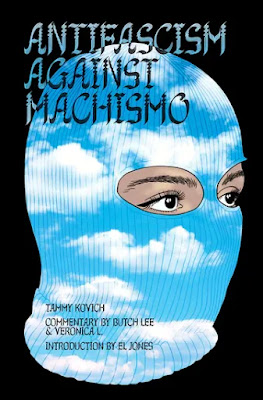

Antifascists confront Proud Boys, Oregon City, OR, 18 June 2021

|

What is increasing, however, is the continued threat of open neo-Nazism and accelerationist violence. Groups like the Goyim Defense League are growing in prominence across the country (but in Florida, in particular), the post-alt-right formation the National Justice Party is filling the gap left by the destruction of the Traditionalist Worker Party, and violent groups like the Rise Above Movement and the Evergreen Active club are offering a novel rebranding of neo-Nazi gang culture. Places like Goyim TV actually are getting more traction than originally thought, and social media sites like Rumble and Telegram are largely insulated from antifascist pressure and are building their brand on refusing to intervene on open racism.

All of these groups have been centered less on public displays of might and more on attempts to interfere with different events built around marginalized identities and institutions they hope to undermine. They have participated in the rapidly increasing protests against LGBTQ and Pride events, particularly any family friendly events or drag shows. This has given them the ability to intermingle with a new generation of activists who are organizing primarily through horizontal social networks on places like Facebook Groups or Telegram as opposed to formal organizations. The organizations that have formed emerged out of these networks and are looser than the top-down structure we saw with many Patriot groups, namely projects like Moms for Liberty and Gays Against Groomers/Trans Against Groomers. While they publicly repudiate white nationalism, their relationships with the far right are extensive and they act as the bridge point where explicit white nationalist and neo-Nazi factions are able to step into the public, participate in larger political expression, and recruit from a potentially friendly right-wing base. This has been the strategy in places like Vancouver, Washington; Oregon City, Oregon; Spokane, Washington; and other places that are not quite as large as Portland or Seattle and have a less developed antifascist culture.

Reflexively, much of the antifascist movement has pivoted to community self-defense, helping to block attacks on queer events, trans healthcare facilities, abortion clinics, and even libraries and schools. These will remain the focal point for far-right attention, so this is driving the reaction from antifascists in the Pacific Northwest. This fundamentally changes the point by which the community is called in and what kind of protest they are called in to do, but it does little to alter the underlying ask: asking supporters to come out and raise the capacity of the actions that use large masses of supporters to defend a particular space.

“Many antifascists have not sought law enforcement solutions for dealing with fascist threats, because when you increase the presence of police, courts, and district attorneys, you also extend the racial and other hierarchies and disparities that are structurally embedded in those systems.”

The second thing that antifascists in the Pacific Northwest are dealing with is something that is also likewise reverberating across the country. Since Trump’s inauguration there have been excessive police crackdowns on left-wing protesters and, in particular, excessive charges and potential sentences given out to those attending demonstrations. The first high profile instances of this were the nearly 200 people arrested for participating in the January 20th, 2017 Inauguration Day protest in Washington D.C., where the police “kettled” protesters to get a huge sweep of attendees into handcuffs and then charged them for the behavior that other, unaffiliated protesters engaged in. The argument was that the protest was inherently a type of criminal conspiracy and so anyone in attendance (and, by accidental arrest, some people who weren’t even in attendance) was aiding and abetting those who took illegal actions like breaking windows and lighting dumpsters on fire. While these charges were ultimately dropped, the kind of felonies that were being leveled at them and the potential sentences attached were draconian enough that they sent shockwaves through antifascist circles.

This trend continued, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, where clashes between antifascists and far-right militants often left the left-wing demonstrators in custody while the right only faced charges for the most egregious acts of violence (and often, not even then). These cases have continued, and there is even one set for the fall in nearby Clackamas County, where an independent journalist was charged with felonies for allegedly defending herself from an attack by a Proud Boy.

These types of charges and sweep arrests defined the 2020 racial justice uprising, where “snatch and grab” arrests were used, as mass charging of serious offenses with little-to-no evidence, and there were frequent attempts to turn those being arrested into informants by offering plea deals weighed against astoundingly long potential sentences.

At the same time, civil litigation may present an even bigger threat. There have been high profile cases of right-wing figures suing antifascist activists, or at least people they believe to be antifascist activists, often with huge sums of right-wing money and countless far-right organizations providing them ample support. The most obvious example of this was this year’s case brought by right-wing media figure Andy Ngo, who was allegedly assaulted while covering an antifascist demonstration in 2019 and who then brought a lawsuit against an assortment of activists, many of whom say they had no role in Ngo’s conflict and were selected seemingly at random. While the case was thrown out for a number of defendants, including all alleged members of Rose city Antifa (which the court said was not an entity that would have legal standing to be sued), several defendants remained when it was time to go to trial. Two ultimately did, John Acker and Elizabeth Richter, who won their trial by showing the claims had no merit. While this was cause for celebration, the reality is that they still owed tens of thousands of dollars in court costs, something that Ngo’s team undoubtedly knew would be the case and was part of their strategy.

Even more shocking, however, is that three defendants were ultimately found civilly liable simply because they did not respond to the charges. Those accused said that they often heard about the accusations very late, had no money or resources to find legal representation (which is not guaranteed in a civil case), and had many other issues that prevented them from actively fighting the charges (such as experiencing homelessness). Now they are on the hook for $100,000 each, showing that the courts will simply award a sufficiently well-funded accuser despite having little evidence of guilt.

These issues only seem to be getting more severe, as a recent case in San Diego shows. In what has been labeled the "San Diego 11," defendants were accused of engaging in conspiracy to riot and other felonies for participating in a protest action at Pacific Beach on January 9th, 2021. The court's claims of conspiracy hinge on the fact that different antifascist demonstrators, who claim they did not know each other or have any coordination, had all engaged with the same social media post. Six of these defendants subsequently took plea deals, which themselves validate the legal repression offered by the district attorney by ensuring that at least some consequences stem from the spurious accusation, but five others remain set on taking this to trial.

There are further developments in the Pacific Northwest that inject additional problems into the mix, and this time it comes largely from progressive politicians. Two “anti-doxxing bills” were introduced in Oregon and Washington, respectively, which criminalize anything deemed as “doxxing,” the release of personal information. Doxxing is a common tactic amongst antifascists, who use it to put pressure on institutions to pull their relationships with white nationalists, thus raising the cost of entry into the white nationalist movement and making it unattractive for new recruits. The far right has tried to do the same thing to antiracist protesters, so liberal legislators brought forward these bills in the name of defending marginalized communities. Despite these intentions, the opposite is likely to be the case. This is part of why many antifascists have not sought law enforcement solutions for dealing with fascist threats, because when you increase the presence of police, courts, and district attorneys, you also extend the racial and other hierarchies and disparities that are structurally embedded in those systems. With the bill close to passage in Washington and now law in Oregon, the ability of antifascists to actually win campaigns will be seriously hindered by this intervention. It looks like groups like the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), which is often criticized for supporting conservatives more frequently than the left, seems positioned to try and challenge these laws in court.

All of this has a cumulative chilling effect on demonstrators, particularly those who simply attend protests rather than organizing. Many of these court cases targeted not the key organizers of a particular event, but just an attendee. What this could do is siphon off participation in the large coalitions and protests that make antifascist demonstrations successful. It could also create internal division, whereby some participants are even more concerned about any potential unlawful civil disobedience or direct action taken by other attendees. The answer to this is likely to establish a larger connection with legal institutions like the ACLU, FIRE, or the National Lawyers Guild, and to win a few high profile cases so that the message will be sent that this is not a viable tactic to use against antifascists. Many activists are noting, however, that the courts are not balanced in their favor, so any strategy based on the idea that they can win numerous court cases may be flawed. There are some efforts to increase what is called “security culture,” such as using pseudonyms or encrypted chat apps like Signal, but it is unclear whether these tools will actually stop a real investigation by state authorities.

On the more positive side, it’s important to acknowledge the incredible strides made by antifascists across the country, but especially in the Pacific Northwest. The reality of the various far-right rallies that happened starting in 2016 is that it forced the left in these cities, like Seattle and Portland, to create the coalitions necessary to respond. Trump has helped to make the case that the threat of the far right is directly attached to the attacks on unions, the environment, tenant rights, and so on. This has helped to create relationships between different organizations and social movements, and those relationships don’t just end when a protest is over. So this has helped build up the tacit coalitions in the area that can respond to issues more quickly and more effectively than they once were. While there has been a decline in large-scale antifascist actions, the capacity is higher than it ever was before.

“Trump has helped to make the case that the threat of the far right is directly attached to the attacks on unions, the environment, tenant rights, and so on. This has helped to create relationships between different organizations and social movements, and those relationships don’t just end when a protest is over.”

Lastly, it’s important to acknowledge the profound changes that we have seen in the tactical self-conception of antifascist organizers. Since the rise of antifascism across the U.S. since 2016, we have seen an astounding amount of violence directed at protesters. For example, in 2020 alone there were well over a hundred car attacks on protesters, which took the form of cars plowing their way into demonstrators. These happened in Portland, as well as shootings, pipe bomb attacks, and extensive violence at protest events. These frightening episodes happened along with a relative indifference (or, in some cases, participation) from police. For example, on August 20th, 2020, a Back the Blue rally was staged in front of the same Justice Center that had seen so many demonstrations against police violence. The police had been heavy-handed with the daily protests for weeks, except on this day they stayed blocks away from the crowd. The far right, including the Proud Boys and people bearing shields, batons, and firearms, attacked the antifascist counter-demonstrators without pause. The police said that protesters should “police themselves,” refusing to intervene on what became a brutal street beating. Later that night, the police returned to their invasive strategy, using batons on protesters themselves. This has sent a clear message to antifascists in the Pacific Northwest: you have to protect yourself. (There was, ultimately, accountability for some of the perpetrators of the August 20th violence, including a prosecution of the lead instigator.)

The effect this has had has been to revive the question of armed community self-defense. At a recent defensive action I attended outside of a drag queen event in Vancouver, Washington, of the 200 demonstrators who attended nearly a third appeared armed. This included semi-automatic weapons staged on the roof of the venue, security teams patrolling with tactical gear, and an open acceptance that firearms would be necessary for (trained) security volunteers to keep the venue safe. All across the country there are armed groups like Yellow Peril Tactical, the John Brown Gun Club, the Huey P. Newton Gun Club, Socialist Rifle Association, Trigger Warning, and others who are employing firearms as part of their defensive mission, the same mission that antifascist mass demonstrations often have had. The use of mass tactics has always had a protective element, and in Portland this was explicitly the mission of groups like Pop Mob, which used really mass protests and marches as a way of ensuring the safety of participants while disrupting the far right. Armed community self-defense, while similar in mission, has a different set of tactics and thus a smaller number of active participants. This has taken on a special importance in the Pacific Northwest given the recent string of far-right assaults, police in action in response, and then a climate and legal framework that is largely friendly to firearms (though that may be changing).

This is by no means a new development, but instead a revival of a well-established one. Armed groups have a long American history amongst marginalized communities fighting against attacks from what we would today consider white nationalists, fascists, or the far right. This took the form of the joint NRA/NAACP chapter led by Robert F. Williams in Monroe, North Carolina, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, and Jewish defense squads led by organizations like the Jewish Labor Bund. The goal is the same as what we are seeing from antifascist groups that stage defensive demonstrations at locations and community events targeted by the far right, but the mechanism is different: in these cases it is armed members that deflect the far right’s advances rather than simply overwhelming masses of people.

There are obvious and defensible reasons for this development, and there are complications introduced by it as well. It will create some difficulty in building the coalitions that have been established over the past several years, most of which were built on an ostensible commitment to strategic non-violence. While armed self-defense groups are not involved in offensive violence, their presence still could be concerning for some partners. This simply means that more community conversations will be necessary to address any conflicted responses and to reestablish the trust necessary to maintain the coalition.

This brings us back to our three questions: what stops the far right, why do we want to stop the far right, and how do our methods lead to our larger goals? By having a vision of the world we want to win we can pick a path to more immediate victories that can act as stepping stones to more systemic change. These are the questions that are guiding the more radical wing of the antifascist movement and will help to determine not just their own future, but the future of the left itself.

Photo credit

Photo by Daniel V. Media. Used with permission.

.jpg)